Brand purpose is a hot topic. Whether you’re a yoghurt maker or professional services firm, defining how your business does right by the world has been one of the major marketing trends in recent years.

Perhaps fueled by noughties cynicism of brands (see the likes of Morgan Spurlock’s “Supersize Me”, or Naomi Klein’s “No Logo”) and the prospect of climate change looming ever larger, businesses have sought to become more actively – and prominently – involved in big environmental and social issues.

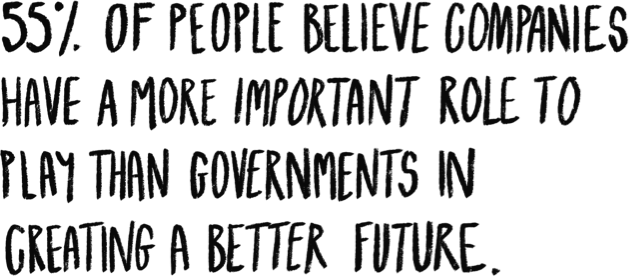

The logic being that behaving in this virtuous way will mean a stronger bond with customers. After all, a recent Meaningful Brands Report by Havas found that 55% of people believe companies have a more important role to play than governments in creating a better future.

But – in the marketing world at least – purpose is proving an extremely divisive concept.

For its proponents, it represents a new way for business to behave ethically and for the greater good of society. They argue that major marketing industry awards such as Cannes Lions are rightly putting greater focus on work that prioritises purpose.

Sceptics reckon that it’s nothing more than a corporate fig leaf, not only failing to address the apparent problems in how business operates but

also distracting from the perfectly legitimate skill of well, just selling stuff. In the B2C world, this position was writ large by Terry Smith – a major shareholder in Unilever – who accused the company of being “obsessed with publicly displaying sustainability credentials at the expense of focusing on the fundamentals of the business.” Smith felt that Unilever would be better served keeping it simple when selling the likes of mayonnaise rather than unnecessarily aggrandising it with brand purpose.

What is a business, anyway?

Underpinning the rationale of brand purpose is the very notion of what a business is. Whilst taking responsibilities like environmental or social impact seriously is nothing new, it’s only in more recent times that this has been crystallised as a central purpose of many brands.

So instead of the bolt-on Corporate Social Responsibility or Sustainability departments of old, brands now seek to put this responsibility front and centre; their ultimate reason for being is not to make profit, but to do good in the world. A prominent B2B example is Deloitte’s stated purpose to “make an impact that matters” – this doesn’t guide a few staff seconded to the basement sustainability department, but informs everything that Deloitte does. However critics have argued that, whilst there is undoubted good in this approach, there’s a fundamental conflict at play.

Nick Asbury points out in a blog on the subject that we’ve had a phrase for organisations with a true purpose for years – they’re called not for profits. Which then begs the question – if an organisation isn’t already operating on a not for profit basis, can it ever truly be committed to an ethical purpose?

Then there is the question of whether a business must have a “true” purpose to be useful to society. Is providing jobs for people and supporting supply chains to do the same not enough in and of itself? Some argue that we shouldn’t downplay this value generated by businesses – there is no need to overlay brand purpose for an organization to be seen as worthwhile. They also contest whether the greater responsibility for improving the world should rest with for profit businesses, who they argue will always have a conflict of interest, or whether this should remain the preserve of politicians, activists and not for profits.

Must a business have a “true” purpose to be useful to society?

Where next?

The result is that the concept of purpose is becoming a loaded term – continuing to accrue negative baggage and distract from the original objective. Case in point: a recent Marketoonist sketch placed “Brand purpose statements” well into the red danger zone on a Marketing B.S. meter.

Perhaps brands will move away from purpose if this continues, but it’s worth bearing in mind that business does not need an ingrained, high level purpose to operate beyond just a pure profit motive. The idea that a business should have other obligations in this regard is not a new one – the likes of Cadbury were practicing what they preached over a century ago.

The key in our experience is to undertake those obligations with honesty – practice responsibility and transparency in what you do. Perhaps that means pursuing a pure brand purpose that guides every fibre of the organisation, but only if that aligns fully with what your business does to generate profit.

In many cases this is simply not going to be possible, and it’s typically that disconnect between what amounts to a neat, fashionable purpose-led brand promise and a different corporate reality that creates the problems. Green-washing, woke-washing, purpose-washing and so on – these all arise from businesses who’ve overreached their responsibilities and actions. The pretence doesn’t tend to last long.